Decompression Illness (DCI), a medical diagnosis that encompasses both Decompression Sickness (DCS, aka “The Bends”) and Arterial Gas Embolism (AGE), is an unfortunate reality that cave divers may be forced to face. Inert gas stress, caused by deep dives and lengthy bottom times, coupled with the exertion of carrying heavy equipment to and from the water, puts cave divers at increased risk of a decompression related injury and it is important that we are well educated on how to identify and care for these maladies.

For several years, the accepted standard of care for DCI was to treat an individual with oxygen while transporting them to a recompression chamber for treatment. However, the Diver’s Alert Network organized a committee to review medical literature regarding triage and various first aid strategies for DCI, and at the 2017 Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society Annual Meeting, a workshop was convened to discuss and review the data. The consensus of the committee members was released in March 2018 in the journal Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine, Vol. 48, Issue 1. In that article is the following statement:

Recompression and hyperbaric oxygen administered in a recompression chamber is acknowledged as the gold standard of care for DCI. However, in locations without ready access to a suitable hyperbaric chamber facility, and if symptoms are significant or progressing, in-water recompression using oxygen is an option. This is only appropriate where groups of divers (including the ‘patient’) have prior relevant training that imparts an understanding of related risks and facilitates a collective acceptance of responsibility for the decision to proceed.[1]

In plain English, the consensus of the committee was that as long certain criteria are met, the use of In-Water Recompression (IWR) as a first aid treatment of DCI may be appropriate. This article aims to review the process to decide whether or not IWR is appropriate, list the criteria that must be met before IWR should be considered, and outline two accepted IWR protocols. However, while it is the intention of this article to introduce an individual to IWR, it is not meant to replace training. Specifically, this article is not a substitute for the training of delivery and use of oxygen underwater (“aka advanced nitrox”), or training in In-Water Recompression.

Deciding if IWR is Appropriate

Categorization and diagnosis of DCI should only be made by a diving medicine physician, and divers should have contact details for communicating with EMS. In the United States, local EMS may be contacted by calling 911, and the Divers Alert Network may be contacted by calling +1-919-684-9111. Triage by telephone with a diving medicine physician at DAN should be used to help categorize a case of DCI as mild or severe.

Mild signs and symptoms of DCI include:

- Fatigue

- Joint and limb pain (note: girdle/trunk pain is suggestive of spinal involvement and does not fall under the classification of limb pain)

- Skin rash

- Subcutaneous (lymphatic) swelling (subcutaneous swelling was added to the definition of mild DCI for several reasons, please see the journal article for the full discussion, however it is noted that the value of recompression treatment for lymphatic DCI, while unknown, is not obvious)

Although mild cases of DCI do not necessarily warrant IWR, there may be some benefit and it should be relatively safe to proceed as long as the criteria needed to engage the IWR protocol are met.

Severe cases of DCI may have neurological symptoms similar to what you may see in a stroke victim, including:

- Numbness and tingling, including in the hands and feet

- Sensory loss, including loss of hearing, smell, and vision

- Slurred speech, including drooping features in the face

- Paralysis and unconsciousness

Additional symptoms of severe DCI may also include:

- Dizziness and nausea, potentially from an inner ear bend

- Respiratory distress and trouble breathing, potentially from bubbles overwhelming the heart and lungs

- Girdle (torso/trunk) pain, potentially indicating a spinal bend

In cases of severe DCI, IWR may be warranted if there is no ready access to a recompression chamber, and all of the criteria to proceed with IWR are in place. However, there are some contraindications that will preclude the use of IWR. To be blunt, IWR should never be considered if any of the following are occurring in the victim:

- Hearing loss / vertigo / vomiting – this indicates a possible inner ear bend, which could result in nausea and vomiting, which could result in a choking or drowning hazard. Return to water would be unsafe.

- Change in consciousness / shock / physical incapacitation – return to water would be unsafe.

- Respiratory distress – return to water would be unsafe.

- Preceding Oxygen Toxicity event – elevated risk of recurrence of Oxygen Toxicity / convulsions / drowning, return to water would be unsafe.

- Diver is unwilling to return for IWR.

Criteria that must be met to proceed with IWR

Assuming that a group has decided it is appropriate to use IWR as first aid for a specific case of DCI, certain criteria must be met before proceeding with the procedure.

A team consisting of, at a minimum, three individuals, should be assembled. The team includes the victim, an in-water tender that will accompany and monitor the victim throughout the IWR protocol, and a surface supervisor. Ideally, there should be a fourth team member that can assist the in-water tender and relay information to/from surface personnel.

Because of the elevated risk of CNS oxygen toxicity from PO2 exposures up to 1.9 BAR, all members of the team should be properly trained and practiced in decompression procedures using 100% oxygen. Specifically, they should understand the risks of, and how to identify the symptoms associated with, CNS oxygen toxicity, and how to properly deal with a convulsion.

The team must have the appropriate equipment for IWR using oxygen. Because cold divers do not decompress efficiently, the diver should have adequate thermal protection that could keep them warm up to four additional hours in the water. The team must also have sufficient oxygen for both the in-water and surface portion of the treatment; at a bare minimum, a team performing IWR on open-circuit scuba should be prepared with 120 cubic feet of oxygen.

The team must have a method to maintain a stable depth for each of the stops, including the slow ascents during stops. A down-line would be very helpful for the ascents between stops.

Finally, the team must have a method of communication (wet-notes/slate).

It is also strongly recommended that the injured diver use a full-face mask, or mouthpiece retaining device, throughout the procedure. However, under no circumstances should divers that have never used a full-face mask use their IWR session as a time to learn new skills — stick with equipment that you use regularly and are familiar with already.

Because the use of breathing gases other than oxygen for IWR is not recommended, IWR should only be accomplished with the patient breathing 100% oxygen. During an IWR procedure, a maximum depth of 30fsw (9msw), should be observed.

Under no circumstances should an individual ever breathe oxygen below 30fsw (9msw) while underwater.

Finally, the entire team must be willing to accept the chance that IWR may not result in complete resolution of DCI, and may in fact cause additional complications due to the exposures to high PO2’s.

Two IWR Protocols

The Wikipedia article on “In-Water Recompression”[2] lists five in-water recompression protocols. Three of the protocols outlined on the Wikipedia page include initial deep spikes to compress bubbles, followed by a gradual ascent to 30fsw (9msw). However, at a TEKDive USA 2018 presentation on IWR, David Doolette discussed that recent data indicates that the efficacy of the deep spike was questionable, and so I will only cover the Australian and US Navy In-Water Recompression protocols here.

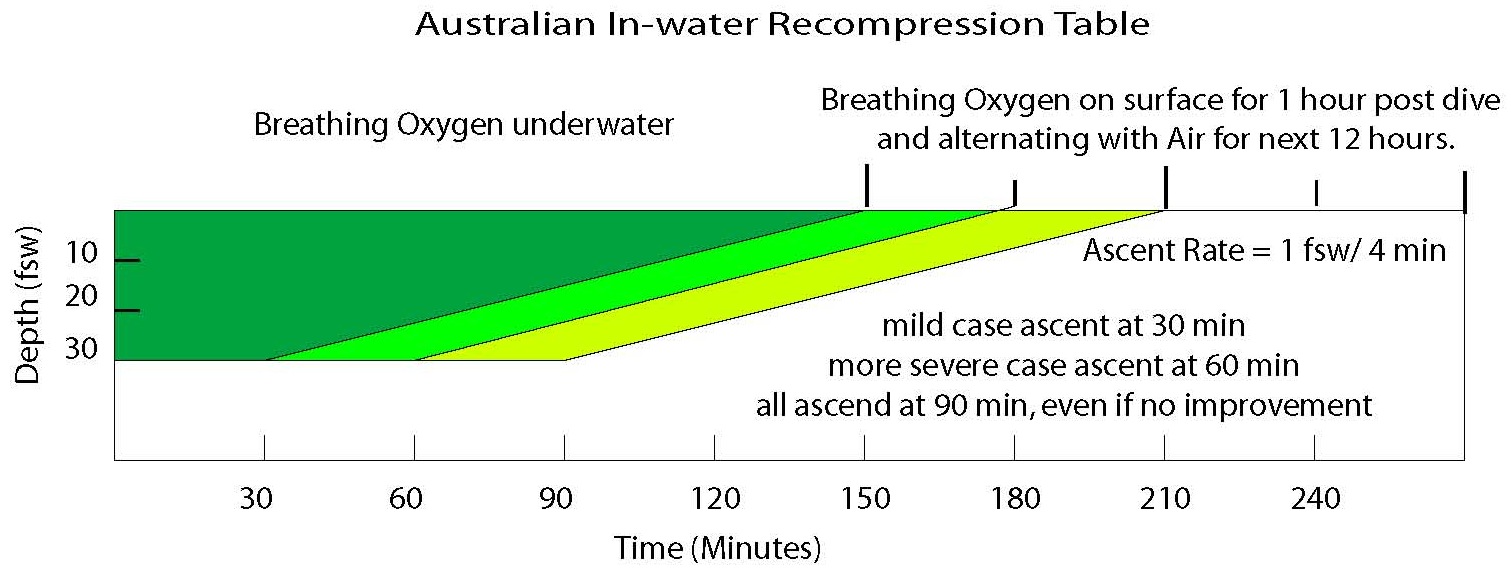

Australian Protocol

The Australian Method was developed by the Australian Royal Navy and was first published in the Journal of South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society in 1979.[3] Under this protocol, oxygen is supplied at a maximum depth of 30fsw (9msw). In mild cases, ascent to the surface can begin after 30 minutes. In severe cases, ascent can begin after 60 minutes if significant improvement has occurred, but if there has been no improvement in significant cases, the time at 30fsw can be extended by 30 minutes to a maximum time of 90 minutes.

During ascent to the surface, the diver remains on oxygen and maintains an ascent rate of 12 minutes per meter (roughly 4 minutes per foot). Once surfacing, the diver alternates between breathing oxygen and air at 1-hour intervals for the next twelve hours.

Total in-water treatment time via the Australian method ranges from a minimum of 150 minutes to a maximum in-water time of 210 minutes.

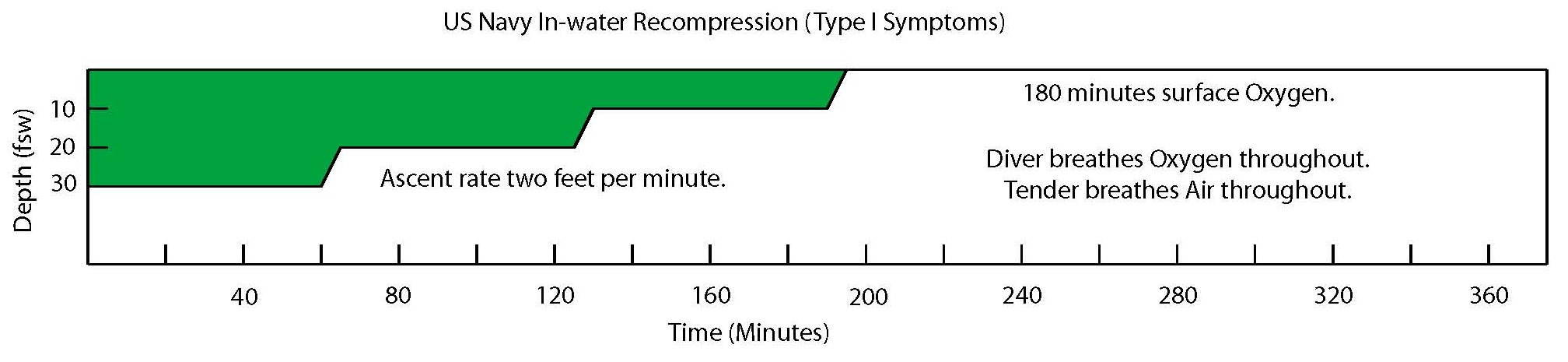

US Navy Protocol

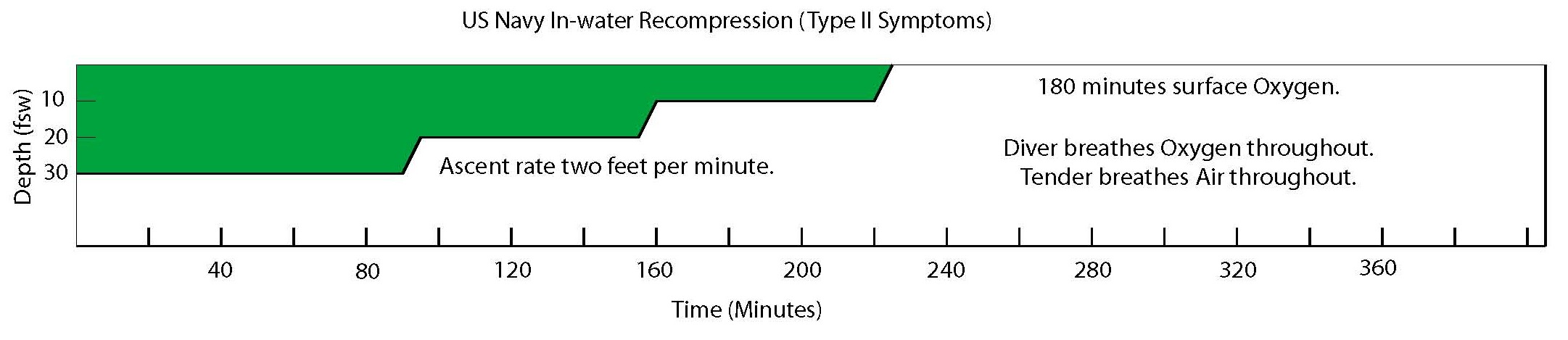

The US Navy developed two IWR treatment tables that are published in the US Navy Diving Manual.[4] The table used depends on the symptoms diagnosed by the medical officer, either Type I (mild) or Type II DCS (severe).

In both tables, the treatment begins at a depth of 30fsw (9msw) with pure oxygen. For mild cases of DCI, an ascent to 20fsw (6msw) begins after 60 minutes, but in severe cases, ascent begins after 90 minutes. After leaving the 30fsw (9msw) stop, the diver ascends to 20fsw (6msw) where the diver will stay on oxygen for 60 minutes before ascending to 10fsw (3msw). Once arriving at 10fsw (3msw), the diver will stay on oxygen for another 60 minutes before making their final ascent to the surface.

The ascent rate between each stop, 30fsw->20fsw, 20fsw->10fsw, and 10fsw->surface is a consistent 2fsw (0.6msw) per minute. Each ascent between stops should take 5 minutes to complete.

When the diver surfaces, they must remain on surface oxygen for 3 hours.

In-water time for the US Navy method ranges from 190 to 220 minutes.

Modifications to the protocols

Both the Australian and US Navy methods were derived to provide treatment for young, physically fit, active, military divers and if you believe you fit the mold, you may find these protocols suitable for use without modification. However, for the benefit of the rest of us, I believe slight modifications to the protocols are worth discussion.

Neither protocol allows for back-gas breaks from oxygen throughout the in-water portion entire procedure. Personally, if I were to use IWR to treat an injury to myself, I would take periodic gas back breaks that align with the same procedure I use during standard oxygen decompression, extending the treatment time accordingly to account for the breaks. For example, if the protocol that I use for back gas breaks calls for a 5-minute break after every 15 minutes on oxygen, a 60-minute stop would be extended by 20 minutes. That schedule would look something like this:

| Description | Gas Being Breathed | Time Remaining |

| Start | Start on Oxygen | 60 |

| 15 minutes “On” | Oxygen | 45 |

| 5 minutes “Break” | Air | 45 |

| 15 minutes “On” | Oxygen | 30 |

| 5 minutes “Break” | Air | 30 |

| 15 minutes “On” | Oxygen | 15 |

| 5 minutes “Break” | Air | 15 |

| 15 minutes “On” | Oxygen | 0 |

Other Protocols

Within the past three years, an article surfaced at several places on the internet, including online diving magazines and a training agency blog. That article recommends descending to a maximum depth of 60fsw (18msw) to begin breathing oxygen while following a US Navy Treatment Schedule 5. I only mention this article because it was fairly wide-spread on the internet, but it is my opinion the article is irresponsible and anyone breathing pure oxygen below 30fsw (9msw) is foolish. Members of the Duke Diving Medicine Team posted the following statement on-line at ScubaBoard, and I believe it is worth quoting here:

The procedure and recompression profile advocated in the article place a diver at grave risk of serious injury or death and should not be attempted. Treatment Table 5 is designed for use in a hyperbaric chamber, not for in-water recompression. For a number of reasons, divers under water are at much higher risk of CNS oxygen toxicity than patients in a hyperbaric chamber, and a TT5 exposes divers to an inspired partial pressure of O2 of 2.82 ATA, far higher than the generally accepted safe immersed exposure limits of 1.3-1.6 ATA. The consequences of a seizure under water while breathing from an open-circuit regulator are obvious, and the article only mentions a full-face mask as a consideration, not a must.[5]

I agree with Duke Diving Medicine and believe nothing more needs be said on this dangerous practice.

In Conclusion

In summary, while IWR may not be suitable for all cases of DCI, it may be an incredibly useful arrow to have in any cave divers quiver. Obviously, the best choice is to get a diver to a proper hyperbaric facility for treatment, but there may be times that this is impractical, if not impossible. The deeply personal decision on whether or not to engage in IWR as a first aid treatment for DCI should only be made after proper categorization of the DCI event has been made by a medical physician, all of the equipment necessary to complete the procedure, including adequate amounts of personnel and oxygen, are assembled, and everyone on the team accepts the risks that are associated with breathing hyperbaric oxygen under water. It should also be noted that there is not a doctor on the planet that will ever recommend IWR as a treatment option for a specific case of DCI, your team will have to make that decision on your own.

It was my goal to help educate you on the review process that must be made before deciding to use IWR, list the criteria that are necessary to begin IWR first aid treatment, and outline two accepted IWR protocols that have been published in several scientific journals. Divers that wish to continue to educate themselves on the subject of IWR may find the Rubicon Foundation Web-site a useful resource and should visit http://rubicon-foundation.org/in-water-recompression/ for more information.

References

[1] “Consensus Guideline: Pre-hospital management of decompression illness: expert review of key principles and controversies.” Mitchell, SJ, et. al. Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine. Vol. 48, Issue 1. pp45-55. http://www.dhmjournal.com/images/ImmediateRelease/Mitchell_DCI-workshop.pdf

[2] In-Water Recompression, Wikipedia Article referenced on April 30, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/In-water_recompression

[3] “Underwater Oxygen Treatment of decompression sickness.” Edmonds, Carl. Journal of South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society, referenced from Rubicon Research Repository on April 30, 2018. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/6221/SPUMS_V9N1_5.pdf?sequence=1

[4] US Navy Diving Manual, Revision 7, Section 17-5.4.2, “In-Water Recompression.” Referenced on April 30, 2018. http://www.navsea.navy.mil/Portals/103/Documents/SUPSALV/Diving/US%20DIVING%20MANUAL_REV7.pdf?ver=2017-01-11-102354-393

[5] ScubaBoard Post on IWR, referenced on April 30, 2018. https://www.scubaboard.com/community/threads/in-water-recompression-revisited.539074/